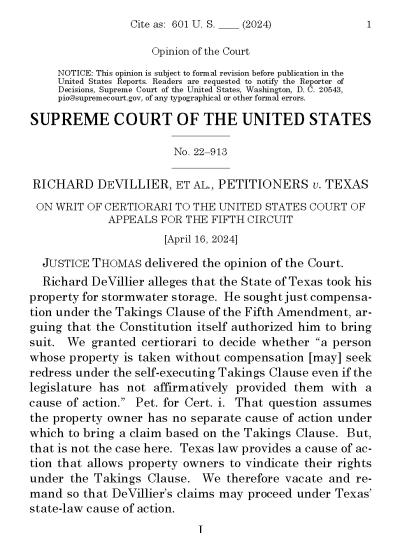

Note: this is the second of our posts on the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision in Devillier v. Texas. The first — which tries to put the weird post-opinion controversy over which party “won” at the Supreme Court into its proper perspective — is here.

In this post we’ll cover the case’s