Latest Post

Next week, we’ll be at the Denver Law School for the 2026 Rocky Mountain Land Use Institute’s “Western Places | Western Spaces” annual conference. Earlier in our career, we were a fairly regular attendee, but for mesne reasons (unrelated to the conference) our ability to attend kind of fell off. Recognizing that shortcoming, we attended the 2025 Conference last year. This convinced us that…

Continue Reading Join Us At The Rocky Mountain Land Use Institute (Denver) To Talk Sheetz, And HousingRecent Posts

Property Rights

Takings

Land Use

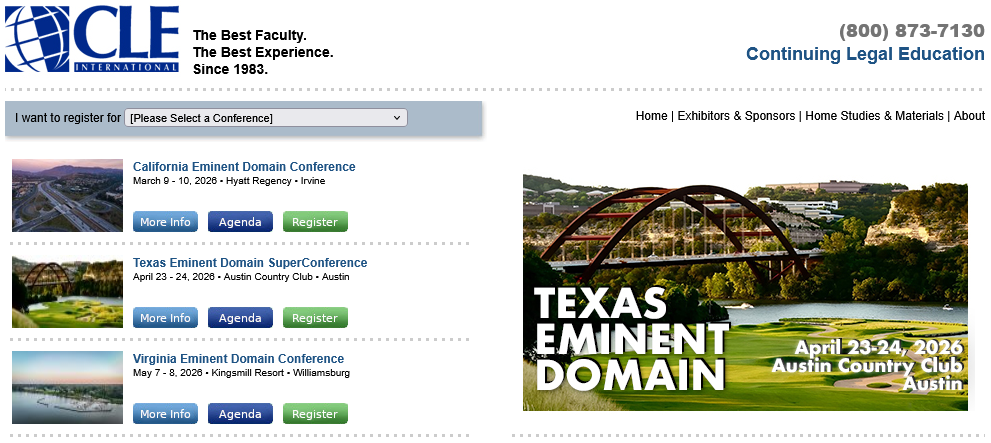

Events & Conferences

Popular Posts