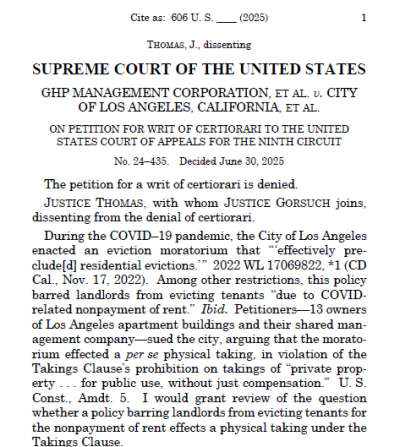

Here’s the latest in a case we’ve been following.

In Englewood Hospital & Medical Center v. State, No A-16-24 (July 16, 2025), the New Jersey Supreme Court rejected physical and regulatory takings claims made by hospitals which are required to treat nonpaying patients even though the Medicare reimbursements available will not cover the hospitals’ costs.

Here’s the bottom line:

Under the facts as presented in this case, we hold that charity care is not an unconstitutional “per se” physical taking of private property without just compensation. It does not grant an affirmative right of access to occupy hospitals; it does not give away or physically set aside hospital property for the government or a third party; and it does not deprive hospitals of all economically beneficial use of their property. We also hold that charity care is not an unconstitutional “regulatory” taking of private property without just compensation.

Continue Reading NJ: Forcing Hospitals To Lose Money To Treat Nonpaying Patients Isn’t A Taking