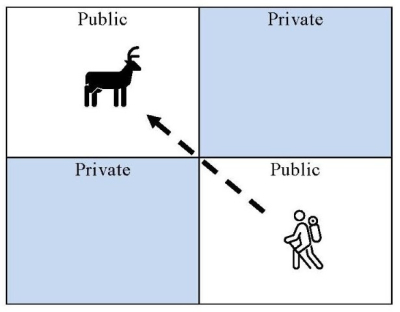

Your Mission: go from Public to Public, without invading Private

Your Mission: go from Public to Public, without invading Private

Here’s the latest in a case we’ve been following from its inception.

This is the “corner crossing” case, which as we noted here, is sure to be a mainstay in future Property Law casebooks, because the checkerboard pattern of public and private land ownership has resulted in a fascinating case. We’re not going to wait for the pocket part, and the case will almost certainly make an appearance in our William and Mary Eminent Domain and Property Rights course in the fall.

Hunters want to access the public lands. This can only be accomplished by crossing at the corners where the parcels connect as shown in the above illustration. Problem is that this cannot be done without trespassing on the private parcels. Even where the hunters go through “Twister“-like contortions to avoid touching the land or violating private airspace. Check this out:

After the Tenth Circuit held that the The private property owner has now filed a cert petition.

Before we go further, here’s the Question Presented:

Between 1850 and 1870, Congress ceded millions of acres of public land in the West to railroads in a distinct checkerboard pattern of alternating public and private plats of land. The result of Congress’s peculiar land-grant scheme is that many parcels of public land in the checkerboard are landlocked and accessible only by “corner crossing”—the act of moving diagonally from the corner of one public parcel to another, trespassing through the adjoining private property in the process.

Nearly fifty years ago, this Court unanimously rejected the government’s argument that Congress “implicitly reserved an easement to pass over the [privately-owned] sections in order to reach the [public] sections that were held by the Government” in the checkerboard. Leo Sheep Co. v. United States, 440 U.S. 668, 678 (1979). In Leo Sheep, that meant the government could not create public access to a Wyoming reservoir by clearing a dirt road that crossed two checkerboard corners—at least not without exercising the government’s power of eminent domain and paying just compensation.

In 2021, four hunters corner crossed through Iron Bar’s property to hunt on public land; Iron Bar sued for trespass. In the decision below, the Tenth Circuit recognized that, under Wyoming law, the hunters had trespassed on Iron Bar’s property. The court nonetheless held that an 1885 federal statute governing fences—the Unlawful Inclosures Act—implicitly preempted Wyoming law and “functionally” created a “limited easement” across privately-held checkerboard land.

The question presented is:

Whether the Unlawful Inclosures Act implicitly preempts private landowners’ state-law property right to exclude in an area covering millions of acres of land throughout the West.

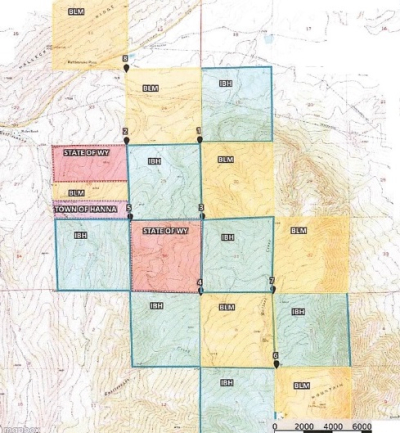

Here are the actual parcels, and some of the corner crossings at issue (again, from the District Court).

The Tenth Circuit started by noting that under Wyoming state law, corner crossings are likely actionable civil trespasses. But the court went on, concluding that the federal anti-fencing statute “preempts” state property law and prohibits the private owners from excluding the hunters. In short, the federal statute and interpreting caselaw “have overridden the state’s civil trespass regime[.]” Id.

In short, here is the Tenth Circuit’s rationale: The owners here have a right to exclude corner-crossers. But the statute says that the public has a right to access public lands, which means any private owner that is getting in the way of that — even where that owner does nothing affirmative to impede public access — is creating a nuisance.

Now the issue has been offered up for Supreme Court review. Stay tuned to see what the Court does with this fascinating case.

Petition for Writ of Certiorari, Iron Bar Holdings, LLC v. Cape, No. ___ (U.S. July 16, 2025)