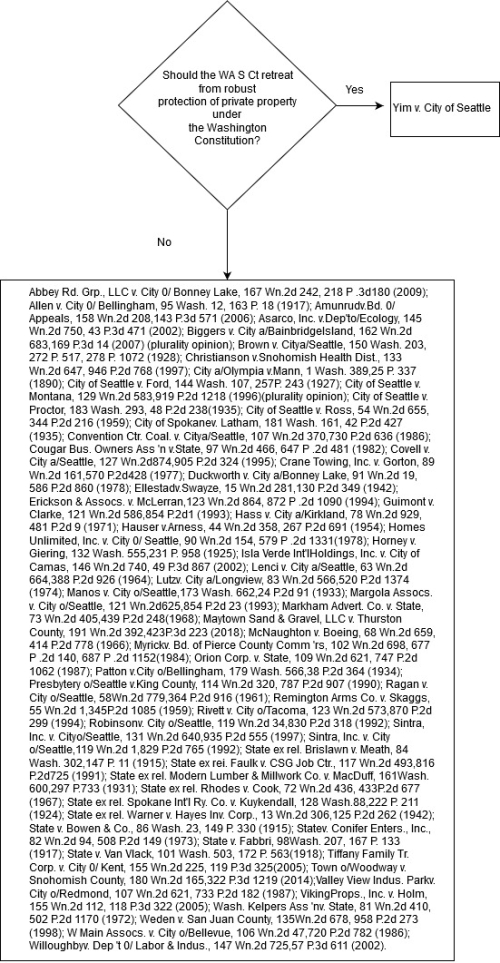

We add a flowchart to this post because the Washington Supreme Court on page 15 of its opinion in Yim v. City of Seattle, No. 95813 (Wash. Nov. 14, 2019) (em banc) (Yim I), includes a flowchart that purports to solve the regulatory takings puzzle once and for all.

Really.

You should check it out. We use “purports” because (surprise, surprise) the court gets it wrong. Flowcharts — also known as decision trees (if A, then B) — are supposed to help, not confuse. And this one doesn’t help if you are trying to figure out if a regulation effects a taking under the Fifth Amendment (and, as a result of the Yim I opinion, under the Washington Constitution).

If that were not bad enough, in a companion opinion in the same matter (on certified questions from the federal court), Yim v. City of Seattle, No. 96817 (Wash. Nov. 14, 2019) (en banc) (Yim II) includes an Appendix listing all of the court’s prior opinions which seemed to hold that under the Washington Constitution, the substantive due process analysis required a more searching judicial inquiry that rational basis review. The court in all of those cases were simply “confused,” and didn’t know what they were doing when they held that private property owners were entitled to greater protections under the Washington Constitution than they are under the due process clause of the U.S. Constitution.

These cases arose out of facial challenges to Seattle’s “first in time” rule for residential leasing. The city adopted an ordinance which requires owners to rent to the first tenant who applies who meets the owner’s screening criteria. In Yim I, the Washington Supreme Court tossed aside long-standing cases that held that the Washington Constitution’s takings clause is not interpreted by the same analysis the U.S. Supreme Court employs for the Fifth Amendment. Not so, held the Yim I court, we might in the future decide that the Washington Takings Clause provides greater protection, but for the time being we conclude that federal takings doctrine is so clear that we simply adopt it wholesale:

Because our prior definition of regulatory takings was not based on independent state law, we need not decide whether it is incorrect and harmful. Instead, “we can reconsider our precedent not only when it has been shown to be incorrect and harmful but also when the legal underpinnings of our precedent have changed or disappeared altogether.” W.G. Clark, 180 Wn.2d at 66. We do so now because two United States Supreme Court cases decided after Manufactured Housing establish that the federal legal underpinnings of our precedent have disappeared, and it has not been shown that there is a principled basis on which to depart from federal law at this time.

Slip op. at 19. The court based this conclusion on Tahoe-Sierra. Really. Of all cases on which to base a conclusion that the U.S. Supreme Court has clarified takings doctrine, Tahoe-Sierra ain’t it. The Washington court, however, was on firmer ground when it cited Lingle as setting forth the idea that the default takings test is the ad hoc analysis of Penn Central. With the federal takings doctrine so clear, the Washington court held that the takings tests under the Washington takings clause are the very same Penn Central, Lingle, and Tahoe-Sierra tests used to measure a regulation under the Fifth Amendment.

Yim II doubled down on this idea, concluding that the test under the Washington Constitution for substantive due process of law is “rational basis” (the federal test) and not (as previously held in the cases cited above) under a slightly heightened standard.

We think that what the court has done in these case is extraordinary. Not content with the independent tests for takings and due process under Washington law — which provided Washington property owners with a modicum of additional protections than under the U.S. Constitution — the Washington Supreme Court has expressly retreated from any recognition that a state constitution can recognize greater civil rights protections. It’s one thing not to go there originally. Many states do that (our state con law is just like U.S. con law). But when a state has a robust — and well-recognized — independent jurisprudence that has been around for a long time, it is truly remarkable when a court in one fell swoop disavows that entire body of law. All on the basis that prior courts were confused.

This of course doesn’t mean that future state law takings challenges to this and other regulations are off the table in Washington. This was a facial takings claim, and leaves open the possibility that an as-applied Penn Central challenge may be brought and successfully prosecuted.

But in its rush to protect the government from future facial challenges, the Washington Supreme Court has, in our view, really done a disservice to the idea that state constitutions are independent and adequate statements of rights that often recognize more protections than the floor of the federal constitution.

Yim v. City of Seattle, No. 95813-1 (Wash. Nov. 14, 2019) (en banc)

Yim v. City of Seattle, No. 96817-9 (Wash. Nov. 14, 2019) (en banc)