We’re spending the day at the alma mater, talking alongside some of the luminaries in the field (lawprofs Thomas Mitchell, Henry Smith, John Inafranca, Thomas Merrill, and Pamela Sameulson, among others) about our favorite topics: dirt law and property rights. This is the “Future of Property Rights” Conference that we mentioned not long ago at the University of Hawaii Law School.

Professor Mitchell started us off with the keynote address, which focused on his work in the “heirs property” field. We saw his emphasis as being on how property rights protect not only the rich and the powerful, but are also important to those on the other end of the economic spectrum. Property rights are civil rights. His work dramatically demonstrates this sense. It was an enlivening and inspirational way to get the conference underway.

We spoke on the first panel along with our PLF colleague Jim Burling and sometimes opposing counsel (but also a friend), Brad Saito (Deputy Corporation Counsel, City & County of Honolulu). (And what appears to be a massive microphone — very Hitchcockian.)

The topic was regulatory takings. Jim walked us through the key issues, including public use in eminent domain, Penn Central, rent control, the upcoming Pung arguments, and access to federal courts for property claims. Brad provided the alternative (government/public) viewpoint.

We spoke about where we think property law, and property rights are heading (after all, the title of the Conference is “The Future of Property”). Here’s a summary of our remarks:

The future of property is bright. Unfortunately, it sometimes gets treated as a hidebound, archaic topic by our nation’s law schools. But property, property law, and property rights law, retain vital importance. If there’s a definition of property, its how we define our relation with the world – a relationship not based on duty (tort), or agreement or reliance (contract), but on either use or exclusion, depending on your preferred theory.

And before we can look forward to property’s future, we need to look back. Maybe not as far back as the Supreme Court seems to do a lot these days with its frequent citations to Magna Carta, Blackstone, and Grotius. But at least to the past century. For it was 100 years ago that the two main threads in constitutional property challenges emerged: Euclid establishing the notion that the rational basis standard meant that the Court was relegating the task of keeping government from acting arbitrarily and capriciously to political processes, while Pennsylvania Coal established the limiting principle that if government action “goes too far” into private property rights, it will be treated as a de facto taking.

Because the Court has not been willing to scale back the rational basis test, or revisit liberty as a fundamental right, the regulatory takings limitation remains the most significant judicial bulwark protecting individual autonomy.

On that topic, I see three big issues in property law and property rights that we should continue to watch for.

Judges or juries. Who makes the call? Will the Court continue to allow the judicial branch to gatekeep private property issues, or will it allow the most populist form of democracy (the civil jury) to determine when justice and fairness require that public benefits be paid for by the public as a whole? We note that the Hawaii Supreme Court recently held that the presumption is that just compensation is determined by juries, and not subject to judicial gatekeeping.

Access to courts. In a similar vein, what is the role of the federal courts in protecting the federal constitutional right of private property? The federal courthouse door was cracked back open again by Knick, and while that case is rightly celebrated for doing so, there’s a lot of work left to do. A very good example of this is a decision from the U.S. District Court for the District of Hawaii holding that the immediate possession procedures in the Hawaii eminent domain code are Erie procedural, and thus not applicable in an eminent domain case removed to federal court.

Second Founding Property. Finally, the third issue to watch is not so much a doctrinal question, but more a policy or vibe thing. Property rights are, as Professor Mitchell reminds us, are civil rights. The originalist approach to private property has focused almost exclusively on the meaning of private property at time of adoption of the Constitution and Fifth Amendment. But equally important is the Fourteenth Amendment’s vision of property under the Due Process Clause, and the importance of private property at incorporation. After all, there’s little question that the first priority of emancipated persons after the Civil War was family reunification, but a close second was the acquisition of private property, for property was viewed as the bulwark against oppression. We should be reminding ourselves that property rights are central to our vision of individual autonomy and freedom.

Professor Inafranca delivered the keynote on the housing panel. His bottom line: optimistic. (We agree.) This photo also reflects the great turnout (both in-person and online).

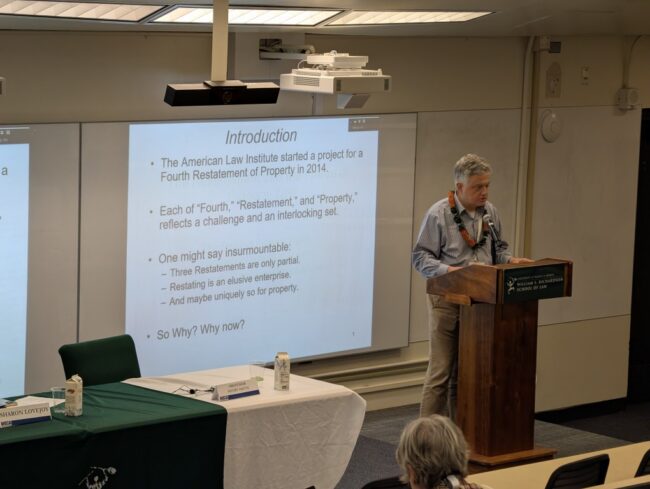

Professor Smith, updating us on the American Law Institute’s Restatement of Property project, which he leads.

Professor Merrill, speaking on coastal zone property, background principles of state property law (and the Lucas decision) and Stop the Beach Renourishment. And the Hawaii Supreme Court’s infamous Kauai Springs case.

As we noted in the preview post, the Conference is not only serving as a great discussion of dirt law, but also a very good excuse to be in Honolulu mid-winter. We were in a dramatically different climate just a short time ago, so the gentle, fragrant breezes that the University of Hawaii at Manoa is known for have been a welcome thaw. And it was good to see a New York colleague whom we last saw in frozen Savannah, who took us up on the suggestion and joined us.