If you understand the headline of this post, congratulations: you are officially so deep in the weeds that you deserve both a Federal Courts and a Takings merit badge.

For those of you not in so deep, here’s the short story behind the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit’s short opinion in Efreom v. McKee, No. 21-1382 (Aug. 18, 2022).

This is one of those pension cases, where the state (here, Rhode Island) shored up its tottering pension system with a new statute that “altered in various ways the retirement benefits to which public employees were entitled, including by reducing the amount and availability of cost-of-living adjustment (“COLA”) payments to retirees.” Slip op. at 4.

As the court noted, “[l]itigation promptly ensured in state court.” Slip op. at 5. Takings claims were included in the lineup. All of the cases were consolidated for trial. Most of the plaintiffs settled. Part of the deal was that the legislature would adopt a new statute that modified some of the cutbacks the challenged statute had put into place.

The court formed a class action to effectuate the settlement, and the plaintiffs in the subsequent federal case were all members of one of the subclasses in that action. They may have had objections to the settlement, but under the local R.I. rules of civil procedure they could not opt out of the class.

After the legislature adopted the statutory modifications, the court approved the settlement over “vigorous” objections, and entered judgment in the class action lawsuit. Appeals to the Rhode Island Supreme Court followed, challenging the procedural aspects (the class action), and the substance of the settlement. The Supreme Court affirmed the judgment on both counts.

Next up, a federal 1983 lawsuit, alleging that the newly-adopted statute (the one adopted in accordance with the settlement agreement) was a taking, and violated the due process and Contracts clauses of the U.S. Constitution. The district court dismissed for failure to state a claim because of res judicata, a lack of standing, and … Rooker-Feldman.

You remember the Rooker-Feldman doctrine (which we’ve dealt with here mostly in the context of judicial takings). Named after the two U.S. Supreme Court decisions which defined its contours, the R-F doctrine says is that U.S. District Courts do not have appellate jurisdiction to review final judgments of state supreme courts.

The First Circuit affirmed that the federal lawsuit was subject to R-F, because the “substance” of the plaintiff’s complaint was a challenge to the R.I Supreme Court ruling:

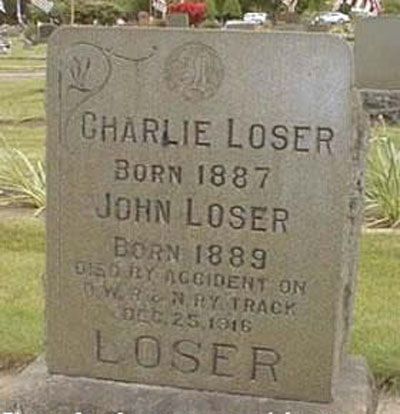

It is just this type of impermissible appellate review that appellants seek in federal court. Dissatisfied with the outcome of the state-court litigation, appellants ask us to set aside the Rhode Island state courts’ approval of the RIPERC class-action settlement, in an action commenced over two years after the Rhode Island Supreme Court rendered its final decision on the matter. It is undisputed that appellants (and defendants) were all parties to the original Clifford action, the RIPERC class, and the final appeal to the Rhode Island Supreme Court in Clifford v. Raimondo. As such, appellants are “state-court losers” seeking, in effect, to review and reverse “state-court judgments rendered before the district court proceedings commenced.”

Slip op. at 14-15 (footnote and citation omitted).

Hold on, the plaintiffs argued, we’re not challenging the Rhode Island decision and asking the federal courts to overturn it, but only the effects of that ruling. See slip op.at 15 (“Appellants nonetheless attempt to escape the vise of Rooker-Feldman by disputing, essentially, that their alleged injuries were actually ’caused by’ the state-court judgments.”). We’re challenging the statute adopted in accordance with the settlement judgment, not the judgment itself, the plaintiffs asserted. This law, they argued, caused a new injury separate from the injuries caused by the state court judgments.

The Fifth Circuit didn’t buy it. The statute, after all, was a direct by-product of the judgment, and “[p]assage of the 2015 Amendments was a condition precedent for the settlement agreement that resolved the state-court litigation.” Slip op. at 16. The statute’s text was “contained verbatim in the settlement agreement,” and the plaintiff’s “attempt to undo the state-court rulings approving the settlement is precisely the sort of ‘end-run around a final state-court judgment’ that the Rooker-Feldman doctrine proscribes.” Id. (footnote omitted).

The court concluded that the plaintiffs are “state-court losers” who sought federal review, albeit indirectly, of the state court’s judgment (even though that judgment was the result of a settlement).

We’re not quite sure what to make of this one. On one hand, the courts have reminded us that the Rooker-Feldman doctrine isn’t a broad rule. It isn’t a general rule against judicial takings claims as the Sixth Circuit concluded. It might cover interlocutory rulings as the same Sixth Circuit concluded (whether it covers settlements is an issue the First Circuit assumed but didn’t really decide here). And it isn’t some catch-all get-out-of-takings-free card, as the Eighth Circuit noted. Yet on the other hand R-F still lives, even if a limited doctrine, as the U.S. Supreme Court reminded in Exxon Mobil Corp. v. Saudi Basic Indus. Corp., 544 U.S. 280, 284 (2005), and maybe this is one of those cases where indeed, the “losers” in state court were merely asking a federal court to overturn the state court loss.

This one seems like a close call, and not one where it is obvious that the case doesn’t belong in federal court. After all, why is this case different than, say, any case that challenging the 2015 statute? Does it matter that the plaintiffs here were involuntary members of the class action the state courts authorized in order to settle the case? (The First Circuit concluded no, it doesn’t matter, but we have to say that our jury is still out on that one.)

Efreom v. McKee, No. 21-1382 (1st Cir. Aug. 18, 2022)