The work of the courts goes on, and as long as there’s stuff to report, we’ll keep reporting as usual.

Yesterday, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit issued an important takings decision in a case and issue we’ve been following for what seems like forever. In Anaheim Gardens, L.P. v. United States, No. 19-1277 (Mar. 25, 2020), the court held that a property owner in a regulatory takings case asserting a Penn Central taking may prove the “economic impact” factor by introducing evidence “by demonstrating their lost opportunity to earn market-rate rental income after prepaying their mortgages.” Slip op. at 17. The Court of Federal Claims had precluded such evidence, concluding instead that the before-the-regulation and after-the-regulation method was the only proper way.

Here’s the short story: the feds adopted programs providing incentives to developers to build low-income housing. The programs offered below-market 40-year mortgages guaranteed by HUD, for example. In return, the owner agreed to limit the rent increases for as long as the HUD guarantee remained in place. The programs also allowed an owner to get out early if after 20 years they prepaid the mortgage. If so, the agreed-upon rent restrictions would vanish.

Perhaps not surprisingly, many owners took that option. Too many owners, in Congress’ judgment. And thus (again, perhaps not surprisingly, also), the feds reacted by eliminating the prepayment option. No prepayment, no conversion of below-market units to market-rate. Takings lawsuits followed.

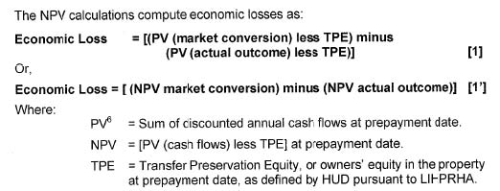

As noted above, the CFC rejected the expert economist testimony offered by the owners. William Wade, Ph.D., (disclosure: Dr. Wade is a colleague of ours, and has guest-blogged before, including posts on Penn Central), testified about the lost opportunity — lost market-rate rental income — that the owners suffered because Congress’ elimination of the prepayment option forced the owners to keep renting at below-market rates. See slip op. at 11-12 for more details of Dr. Wade’s testimony. See also the graphic above.

Nope, held the CFC:

Despite Dr. Wade’s opinions, the Claims Court found that Dr. Wade’s analysis was nonprobative of economic im-pact under Penn Central. First, the court found that Dr. Wade’s lost income analysis was nonprobative because he was required to analyze and compare fair market values. Decision, 140 Fed. Cl. at 89 (“[FWPs] have not established the fair market value (FMV) of the FWPs’ properties at the time of the taking, for either the scenario where the mortgage prepayment right was unrestricted, or the scenario where the mortgage prepayment right was restricted by LIHPRHA.”). And second, the court found that “Dr. Wade’s methodology is unsound because it is inconsistent with binding precedent,” in particular relating to “the parcel as a whole concept” and “economic loss severity measures.” Id. at 89–91.

Slip op. at 13.

“[G[uided by the Supreme Court’s cautions against rigidity in this area of law,” slip op. at 14, the Federal Circuit rejected the CFC’s categorical rule, holding instead that “courts must have flexibility to determine in each individual case how to most accurately measure the economic value of what a takings claimant actually lost due to the governmental action.” Slip op. at 15. Yes, “before and after” the regulation might serve the purpose of determining the economic impact of the regulation, but it isn’t the sole way to approach it. Lost net income, discounted to present value, also could work. “Neither approach appears to be inherently better than the other.” Id.

The difference between temporary takings (as were at issue in prior Federal Circuit cases), and the permanent nature of the takings here did not matter. Yes, permanent vs temporary can affect the analysis. But it isn’t determinative of the of the method used. Slip op. at 16 (“Regardless whether a taking is permanent or temporary in nature, there is no one-size-fits-all method for measuring the economic impact of a governmental action.”).

As for our post’s title, one of the property owner/plaintiffs in the case was an outfit known as “620 Su Casa Por Cortez,” which was in a slightly different position than the other plaintiffs. Su Casa didn’t own its property prior to the time Congress changed the early-redemption rules, but bought subject to those rules. So yes, you guessed it, in Su Casa’s case, the CFC held that purchasing the property already subject to the allegedly restrictive regulation means it failed the “investment-backed expectations” Penn Central prong also.

Unlike the Federal Circuit’s conclusion that the CFC got it wrong on the “economic impact” Penn Central prong, here the court agreed with the CFC. It rejected Su Casa’s argument that Palazzolo rejected the “subsequent transfer” holding:

The governmental action in this case is the enactment of the Preservation Statutes. Su Casa purchased its property in an arms-length transaction after it already knew that the Preservation Statutes had eliminated the prepayment option that previously existed under the 1961 amendments to the National Housing Act. While the HUD regulations had not yet gone into effect at the time of the transaction, the Preservation Statutes themselves were sufficiently detailed to remove any reasonable expectation that Su Casa could have had that it would have the option to prepay its mortgage and convert its property from low-income housing to a market-rate rental property.

Su Casa’s reliance on Palazzolo v. Rhode Island, 533 U.S. 606 (2001), is inapposite. . . .Here, unlike in Palazzolo, the Claims Court did have occasion to consider whether Su Casa could prove reasonable investment-backed expectations in view of the timing of its purchase and its knowledge about the Preservation Statutes. The Claims Court determined, not as a per se rule but rather as an evidentiary failure, that Su Casa lacked sufficient evidence to prevail at trial.

Slip op. at 8. Hmmm…ok. We’ll have to see about that one. After all, the Supreme Court in Murr did say that purchase subject to restrictions is “a factor” in investment-backed expectations analysis. But that has always seemed more like a way to back into a per se rule, than an actual distinction to us. Maybe this is the case to take back up on that issue?

Please read the entire opinion. There’s a lot there, obviously. And it is a good distraction from the swirl of the 25/7 news cycle that is making everyone just a bit crazy.

Anaheim Gardens, L.P. v. United States, No. 19-1277 (Fed. Cir. Mar. 25, 2020)