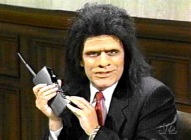

Remember Phil Hartman’s classic Saturday Night Live routine, “Unfrozen Caveman Lawyer” —

Remember Phil Hartman’s classic Saturday Night Live routine, “Unfrozen Caveman Lawyer” —

One hundred thousand years ago, a caveman was out hunting on the frozenwastes when he slipped and fell into a crevasse. In 1988, he wasdiscovered by some scientists and thawed out. He then went to lawschool and became… Unfrozen Caveman Lawyer.

We can’t summarize the skit any better than wikipedia:

The running gag was that [Hartman] would speak in a highly articulateand smoothly self-assured manner to a jury or an audience about howthings in the modern world supposedly “frighten and confuse” him. Hewould then list several things that confounded him about modern life orthe natural world, such as: “When I see a solar eclipse, like the one Iwent to last year in Hawaii, I think ‘Oh no! Is the moon eating thesun?’ I don’t know. Because I’m a caveman — that’s the way I think.”This pronouncement would seem ironic, coming from someone who had, forexample, just ended a brisk cell phone conversation, or indeed attendedlaw school.

According to a 6-1 majority of the New York Court of Appeals in Goldstein v. New York State Urban Development Corp., No. 178 (Nov. 24, 2009), New York judges are similarly so “frightened and confused” about the meaning of the term “substandard and insanitary” in the state constitution that they are incapable of reviewing takings which purportedly remedy blight:

It is important to stress that lending precise content to these generalterms has not been, and may not be, primarily a judicial exercise. Whether a matter should be the subject of a public undertaking — whether its pursuit will serve a public purpose or use — is ordinarily the province of the Legislature, not the Judiciary, and the actual specification of the uses identified by the Legislature as public has largely been left to quasi-legislative administrative agencies. It is only where there is no room for reasonable difference of opinion as to whether an area is blighted, that judges may substitute their views as to the adequacy with which the public purpose of blight removal has been made out for that of the legislatively designated agencies; where, as here, “those bodies have made their finding, not corruptly or irrationally or baselessly, there is nothing for the courts to do about it, unless every act and decision of another departments of government is subject to revision by the courts.”

Slip op. at 16 (quoting Kaskel v. Impellitteri, 306 N.Y. 73, 78 (1953), cert. denied, 347 U.S. 934 (1954)). Article XVIII of the New York constitution allows the state’s eminent domain power to be used to rehabilitate blighted areas:

Subject to the provisions of this article, the legislature mayprovide in such manner, by such means and upon such terms andconditions as it may prescribe for low rent housing and nursing homeaccommodations for persons of low income as defined by law, or for theclearance, replanning, reconstruction and rehabilitation of substandardand insanitary areas, or for both such purposes, and for recreational andother facilities incidental or appurtenant thereto.

N.Y. Const. art. XVIII, § 1 (emphasis added).

The property owners challenged a taking by the Empire State DevelopmentCorporation, asserting that ESDC’s blight designation was overbroad and included both blighted and nonblighted properties in the footprint of the proposed AtlanticYards project in Brooklyn. While some portions of the project area were admittedly “substandard and insanitary,” their properties were not, by any stretch of the imagination.

We’re not going to summarize the facts of the case; others have done that very well here (Wall Street Journal), here (Village Voice), here (Law of the Land blog), here (NJ Eminent Domain Law Blog), and here (Atlantic Yards Report). Or, you can read the court’s opinion (which omits certain facts you might think would be critical, such as the rationalefor the taking was, at first, economic development, and onlybecame “blight” remediation after a year into the project). You can also check out the oral argument video here, the archive of our live blog of the arguments here, and the post-argument analysis here.

The court concluded an agency’s blight determination is essentially immune from judicial review because the task of judging what properties are blighted has been delegated by the constitution to the legislature. Slip op. at 18 (“The [New York] Constitution accords government broad power to take and clear substandard and insanitary areas for development. In so doing, it commensurately deprives the Judiciary of grounds to interfere with the exercise.”). While the majority cast a skeptical eye on the blight finding, it nonetheless refused to get involved:

It may be that the bar has now been set too low — that what will now pass as “blight,” as that expression has come to be understood and used by political appointees to public corporations relying upon studies paid for by developers, should not be permitted to constitute a predicate for the invasion of property rights and the razing of homes and businesses. But any such limitation upon the sovereign power of eminent domain as it has come to be defined in the urban renewal context is a matter for the Legislature, not the courts.

Slip op. at 17. The dissenting judge had a different view, noting that judges are not very frightened and confused when it comes to judicial review of other parts of the constitution, and there is no reason to believe that they are not up to the task when it comes to “public use” or blight:

The right not to have one’s property taken for other than public use isa constitutional right like others. It is hard to imagine any courtsaying that a decision about whether an utterance is constitutionallyprotected speech, or whether a search was unreasonable, or whether aschool district has been guilty of racial discrimination, is notprimarily a judicial exercise. While no doubt some degree of deferenceis due to public agencies and to legislatures, to allow them to decidedthe facts on which constitutional rights depend is to render theconstitutional protections impotent.

Dissent at 11 (citing NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware Co., 458 U.S. 886, 915 n.50 (1982); Ker v. California, 374 U.S. 23, 34 (1963)).

On one hand, the majority’s conclusion is old hat: that a condemnor may throw out the baby with thebathwater has been a part of redevelopment takingssince at least Berman v. Parker,348U.S. 26 (1954), the case in which the U.S. Supreme Court held that anon-blighted store could be taken as part of a larger redevelopmentproject designed to remedy urban blight. TheCourt reached this conclusion by equating the power of eminent domainwith the police power, and by characterizing the non-blightedproperties as a part of the problem, even if they were not dilapidated.See id. at 35 (“The experts concluded that, if the communitywere to be healthy, if it were not to revert again to a blighted orslum area, as though possessed of a congenital disease, the area mustbe planned as a whole. It was not enough, they believed, to removeexisting buildings that were insanitary or unsightly.”).

Had the Goldstein court simply adopted Berman‘srationale and applied it to the New York Constitution’s takings clause,the opinion would not be particularly unusual.

The Goldsteinmajority, however, did not hold that the Atlantic Yards taking could condemn blighted aswell as nonblighted properties, but concluded that courts must accept an agency’s determination that a parcel is in fact blighted. The court’s total deference to thestated reasons for a taking establishes a standard so minimal, it isdoubtful that even the majority in Kelo v. City of New London, 545 U.S. 469 (2005) would likely accept it.

At least two state courts — the District ofColumbia and Hawaii — have viewed the Fifth Amendment and Kelo as requiring substantial deference to alegislative determination that a class of uses is a public use, but reserving for judicial review under the the Public Use Clause the question of whether a particular use or purpose is in fact the reason for a taking. See Franco v. Nat’l Capital Revitalization Corp., 903 A.2d 160, 169 n.8 (D.C. 2007) (“appply[ing] the decision of the Kelo majority, written by Justice Stevens,” a claim of pretext should be taken seriously and a court has the power of judicial review); County of Hawaii v. C&C Coupe Family Ltd. P’ship, 198 P.3d 615, 644 (Haw. 2008) (“However, both [Haw. Hous. Auth. v.] Ajimine[, 39 Haw. 543, 550 (Terr. 1952)] and Kelo make it apparent that, although the government’s stated purpose is subject to prima facie acceptance, it need not be taken at face value where there is evidence that the stated purpose may be pretextual.”). [Disclosure: we represent the property owners in the Coupe cases.].

These cases stand somewhat apart from other post-Kelo decisions which hold that the public use clause in a state constitution provides greater protection to property owners than does the Fifth Amendment. See, e.g., City of Norwood v. Horney, 853 N.E. 1115 (Ohio 2006) (economic development alone will not support a taking under the Ohio Constitution); County of Wayne v. Hathcock, 684 N.W.2d 765 (Mich. 2004) (same, under the Michigan Constitution’s public use clause). Both Franco and Coupe concluded that the Fifth Amendment and the majority opinion in Kelo require meaningful judicial review.

Thus, the Goldstein majority’s assertion that judges have virtually no role in reviewing claims that property is blighted arguably falls below even Kelo‘s standard, and reminds us of Hartman’s unctuous, insincere cave man:

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury…I’m just a cave man. I fell insome ice and later got thawed out by some of your scientists.

Yourworld frightens and confuses me!

Sometimes, the honking horns of yourtraffic make me want to get out of my BMW and run off into the hills,or whatever. Sometimes when I get a message on my fax machine I wonder: did little demons get inside and type it?

I don’t know! My primitive mind can’t grasp these concepts.

The minds of New York judges may not be able to grasp what “substandard and insanitary” property looks like, but it seems like a lot of other minds can.