Here’s one we’ve been waiting to drop. In KMS Retail Rowlett, LP v. City of Rowlett, No. 17-0850 (May 17, 2019), a deeply divided Texas Supreme Court held that a statute — adopted in response to Kelo — which seems to limit eminent domain power, also contains a massive hole: according to the court, it doesn’t apply to “transportation projects.”

The statute — Texas Gov’t Code § 2206.001 — bars four kinds of takings:

- if the taking confers a private benefit on a specific private party

- if the taking is pretextual, and although it purports to be for public use, is actually for private benefit

- economic development takings

- if the taking “is not for a public use”

But the statute also provides, “[t]his section does not affect the authority of an entity authorized by law to take private property through the use of eminent domain for: (1) transportation projects, including, but not limited to, railroads, airports, or public roads or highways…”

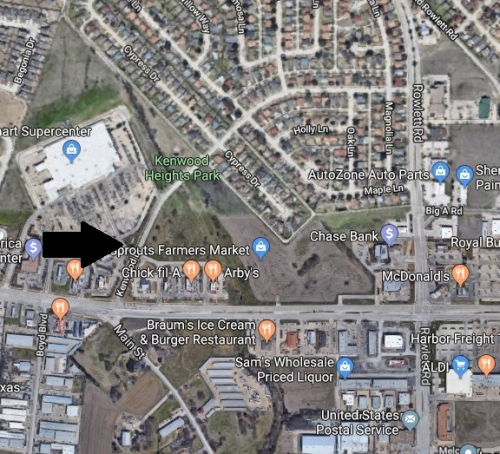

As part of a deal to “recruit” a “Sprouts Farmer’s Market (a “high quality” grocery store), Rowlett (a municipality near Dallas), condemned KMS’s property — a private easement used to access KMS’s existing site (see arrow on the photo above) — to “convert it to a public road connecting several commercial retail and restaurant sites.” Slip op. at 1.

KMS objected, arguing “that Briarwood [the adjacent owner on whose property the grocery store was to be located] and the city colluded to have the city condemn what Briarwood could not acquire on its own after Briarwood learned it had no easement allowing it to extend the private drive and failed to negotiate purchase of the necessary land.” Slip op. at 3-4. KMS argued this was a taking “solely to benefit a private entity.” Slip op. at 4.

Commissioners established the compensation owed ($31k), the trial court granted the city summary judgment on public use and necessity, and denied KMS summary judgment on bad faith taking. The court of appeals affirmed. Check out the briefs of the parties and amici, and the oral argument video if you want the details of their positions when the case reached the Texas Supreme Court.

The court acknowledged that section 2206 was “a swift legislative response to Kelo.” Slip op. at 8. But the court rejected the owner’s argument that the statute altered the usual approach of judicial deference to the legislature’s pronouncement of what is a public use and what is necessary. At least for transportation projects. After all, “KMS’s easement was indisputably taken to facilitate construction of a public road.” Slip op. at 10.

The court didn’t buy the pretext-within-a-exception argument that this wasn’t a “legitimate transportation project,” and therefore it should look at the city’s stated use with a keener eye. Check out pages 12-14 for the court’s analysis of the statute’s language. Here’s what we think is the key takeaway from that portion of the opinion:

Accordingly, if a taking is for a transportation project, the condemnor is constrained only by the statutory provisions that grant it condemnation authority (and any other relevant statutes) and the limitations imposed by the constitution and our case law. The condemnor is free of the additional limitations imposed by section 2206.001(b).

Slip op. at 12-13. The court also rejected KMS’s argument that this reading guts the point of the statute, allowing condemnors to escape heightened scrutiny simply by declaring that a project is for “transportation.” True, but too bad:

KMS’s point is well-taken, but sometimes that is how exceptions work, whether inadvertently or by design. The simplest explanation for the exception is that the legislature sought to provide greater statutory limitations on takings for “economic development purposes” that were the subject of the Kelo decision while maintaining the status quo for more traditional takings purposes.

Slip op. at 13. The court concluded that this was a “transportation project” because it involved a road, and therefore the exception governed.

The court also examined the situation under the Texas Constitution’s public use requirement without reference to the statute. The court concluded that even though there was some private benefit (boy howdy there was) the conversion of the driveway into a public road would have some traffic benefits. And you know what that means: “[w]e are therefore not presented with any basis on which to disagree with the court of appeals’ conclusion that ‘[t]raffic circulation and cross-access between retail areas is a public purpose.’ The evidence the court of appeals considered establishes that the taking was for a public use.” Slip op. at 20. The Supreme Court also reject KMS’s argument that the taking was not necessary to further the public use.

As for the bad faith/fraudulent taking claim, the court concluded that KMS’s motion for summary judgment that the city had an ulterior motive didn’t get it where it needed to go, because KMS did not claim that the private benefit was the sole reason for the taking:

Here, KMS’s argument that the economic-incentives agreement played a role in the taking does not negate any of the city’s ostensible public uses justifying the taking. Rather, KMS’s argument merely points to an additional, unstated private benefit the city arguably conferred on Briarwood, Sprouts, or both. So the question becomes whether the city’s alleged desire to benefit a private entity negates a taking based on otherwise indisputably valid public uses. Put another way, is the taking fraudulent if the alleged private benefit does not negate the ostensible public use but simply suggests an additional motive behind the taking?

Slip op. at 26.

Nope, the presence of private benefit doesn’t negate the public character of the taking. The private benefit must be the “only” reason for the condemnation. Id. (“The taking here plainly benefits the public at large even if it also privately benefits Briarwood and Sprouts.”).

Three justices dissented, arguing that the 2009 post-Kelo amendments to the Texas Constitution — intended to constitutionalize the O’Connor and Thomas Kelo dissents — require less-deferential judicial review. The majority was “not unsympathetic” to this argument, but was “reluctant to explore this potentially fertile ground here because, simply put, no one has asked us to.” Slip op. at 30. Cue Justice O’Connor (“maybe you should have”). Bring it on, the majority concluded:

A change to the constitution itself, however, can prompt us to revisit prior decisions. But KMS never urges us to consider the impact of the 2009 constitutional amendment on our public-use jurisprudence. JUSTICE BLACKLOCK does so ably in dissent, and we would welcome the opportunity to further explore his position in a future case in which the issue is directly presented.

Slip op. at 31.

Does the section of the majority’s opinion that deals with pretext and whether a smidgen of public use will save a taking that has lots of private benefit invite a SCOTUS cert petition? Maybe so, and given the amicus players in this case, we would not be surprised to see one.

KMS Retail Rowlett, LP v. City of Rowlett, No. 17-0850 (Tex. May 17, 2019)