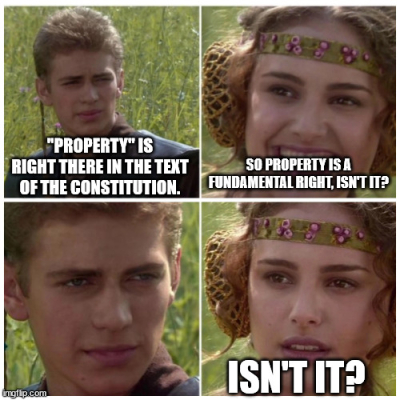

To us, one of the strangest things in constitutional law is the conclusion that although private property is a fundamental right for purposes of the Just Compensation Clause, it isn’t fundamental for purposes of the Due Process Clause. When your private property is taken you must be provided compensation. But when you are deprived of property, all you get is rational basis review. But both “property” and “private property” are right there in the text of the Constitution. How can courts conclude that a property right isn’t fundamental?

Doesn’t compute for you either? The lower courts are indeed all over the place on this one. Check out cases like this one, and compare the reasoning to cases like this one.

Last week, our firm filed a cert petition asking the Supreme Court to take up the issue. The case involves property owners’ Due Process challenge to the City of Seattle’s ordinance that forbids owners from considering a prospective tenant’s criminal history when deciding whether to let that person occupy rental property.

This one is one of ours, so we won’t be commenting on it in any detail. But here’s the Question Presented:

The City of Seattle’s “Fair Chance Housing Ordinance” declares it unlawful for private property owners to consider a prospective tenant’s criminal history when deciding who may occupy their property—even though criminals are substantially more likely to reoffend in and around their residences. The Ordinance bans such consideration regardless of the gravity of an applicant’s crimes, the number of convictions, the time since the last conviction, or other indicators that the applicant poses a risk of harm to an owner’s family or other tenants, and the Ordinance furthermore subjects owners to massive civil penalties for considering that history when selecting tenants. The City exempts itself and other public housing providers from these restrictions.

Chong and MariLyn Yim own a triplex in Seattle. As is often necessary in housing-deprived cities nationwide, the Yims and their three children shared their living and intimate spaces with tenants—they live in one unit and rent the other two. The Ordinance deprived the Yims of their fundamental right to safeguard their home, to keep dangerous convicted criminals out of their property, and of their obligation to protect their children and their tenants.

The question presented is:

Does Seattle’s restriction on private owners’ right to exclude potentially dangerous tenants from their property violate the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause?

Stay tuned. Follow along here, or on the Court’s docket.

Petition for Writ of Certiorari, Yim v. City of Seattle, No. 23-239 (U.S. Sep. 26, 2023) by RHT on Scribd