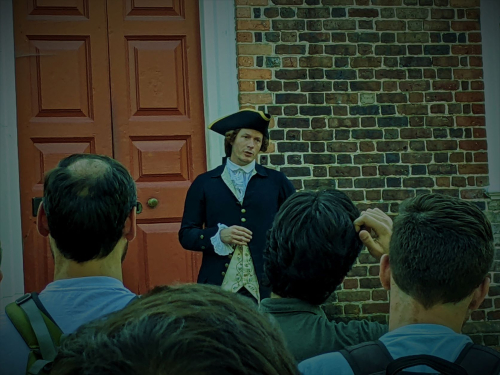

Introduced on George Wythe’s steps.

One of the (many) great things about teaching and studying law at the William and Mary Law School is the location. A short walk from historic Williamsburg, the Law School (the nation’s first law school, by the way) is at the center of where some very important property events took place.

So it was last evening. The W&M Legal History Society asked Thomas Jefferson, Esq., an up-and-coming local Williamsburg lawyer to speak to a group of law students and lawprofs, offering his thoughts about the profession. He even was eager to respond to some very difficult questions about his life, his philosophy and politics, and his personal conduct.

Meeting on the front steps of Jefferson’s mentor George Wythe’s home, we got to know a bit more about Mr. Jefferson’s W&M training, his legal apprenticeship under Mr. Wythe, and some of the lawsuits in which he was counsel.

A Glorious Revolution? Perhaps.

A glorious late summer day in The Burg? Certainly.

The long summer evening stretched out and the breeze was cool, so we walked a short distance to a more intimate setting, one of the stately oaks that dot central Williamsburg, where Mr. Jefferson spoke about the Declaration of Independence, the Lockean theories behind it, and how he considers it his crowning achievement (our words, not his).

Explaining that he too had to take a bar examination.

Sorry, kids.

Our discussion about the Declaration and its timeless words about “all men are created equal” with unalienable rights including (inter alia) the rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness prompted some questions from the audience. What do you mean when you wrote “pursuit of happiness,” and how might it differ from the more traditional (Lockean) formulation of life, liberty, and property? What were you thinking?

Using pursuit of happiness, he explained, was his way of suggesting that the purpose of government isn’t limited to securing the right to property, but to something larger. Of course, acquiring and possessing property is a large part of happiness, but isn’t all of it. It ties back to the notion that all men are created equal, he noted, because it includes people without property.

That prompted some related follow-ups about Mr. Jefferson’s personal conduct. Forgive me for what might be an impolitic question, but how can someone who writes such words, Sir, also treat other equal men as property? How should we today look at you? Words not deeds, hero or sinner?

To his credit, he was candid about his faults and responded frankly. He was hardly perfect, or even good. Acknowledging his personal hypocrisy, but also pointing out that he was considered a class traitor at the time by his Virginia and southern peers for even suggesting that slavery should be abolished (as proposed by his draft Virginia Constitution, authored at the same time as the Declaration but never adopted), and for including a section in the draft Declaration (also stricken from the final version) pointing the finger at His Britannic Majesty for saddling the colonies with with what he described as a “cruel war against human nature itself,” that violated the “most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended.”

Pointing out as well a case from his Williamsburg law practice (“which I argued over in that building” he noted, pointing to the actual courthouse in which the Virginia General Court, the highest court in the Colony sat), Howell v. Netherland (1770). There, Jefferson argued for more freedom not less, in case involving the legal indentured servitude of the grandchild of a mixed-race couple. He pointed out that his mentor Wythe represented the master (small town barrister practice often means you take the case as it comes, with your friends taking the other party), and that Jefferson lost the case. All of the above, Jefferson suggested, should count for something when history judges me. We shall see, Sir.

Jefferson also spoke about other issues, such as republicanism vs democracy, public virtue, the study of law, and even about his long-lost favorite violin.

Sidebar: the fellow portraying Jefferson is outstanding, and looks and acts and speaks in a manner of what we imagine Jefferson to have been like, right down to acknowledging that he was not a great orator and expressed himself better in writing. He never broke character, and played his part so well that at times we had to remind ourselves that this was an actor, and not the actual guy standing before us.